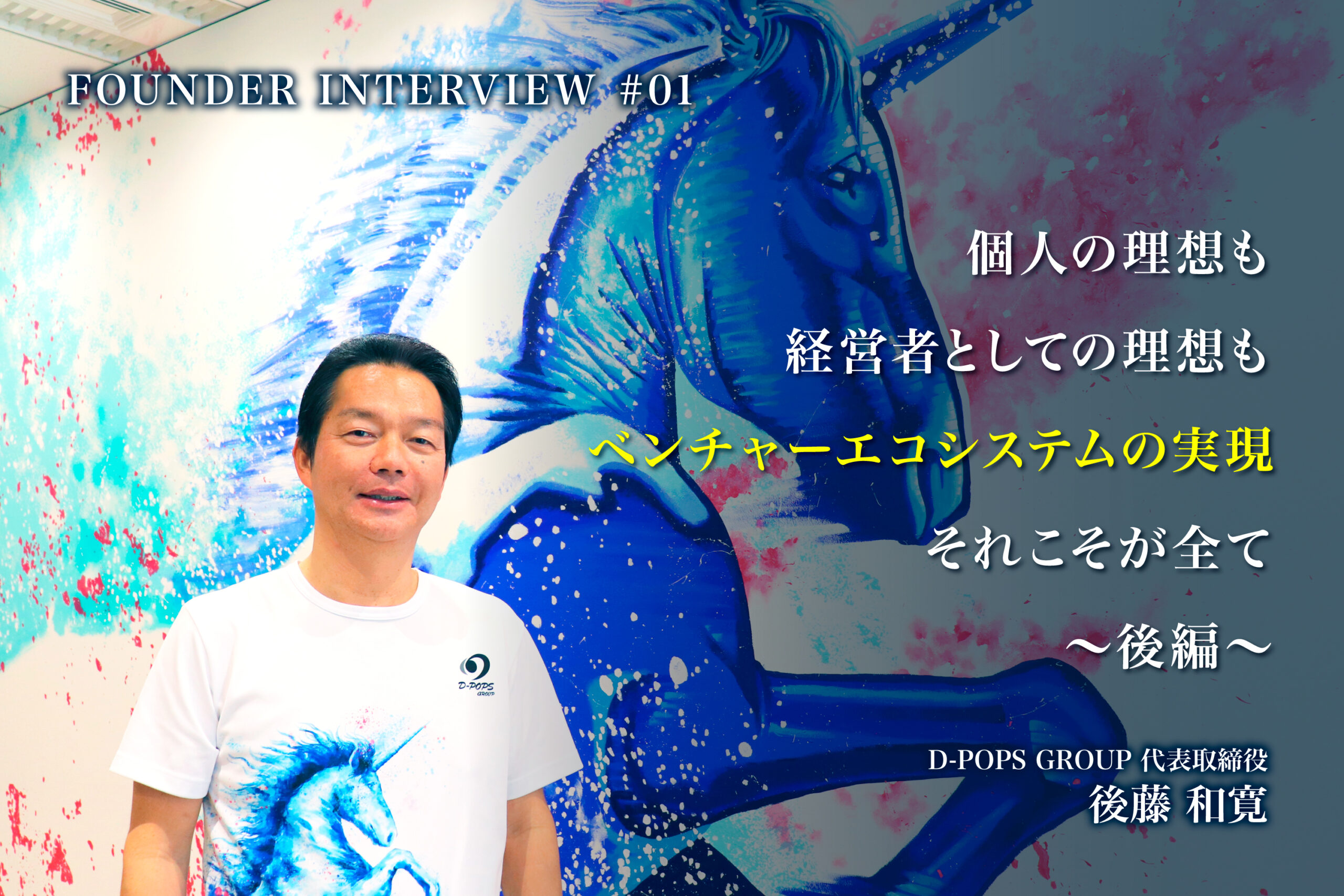

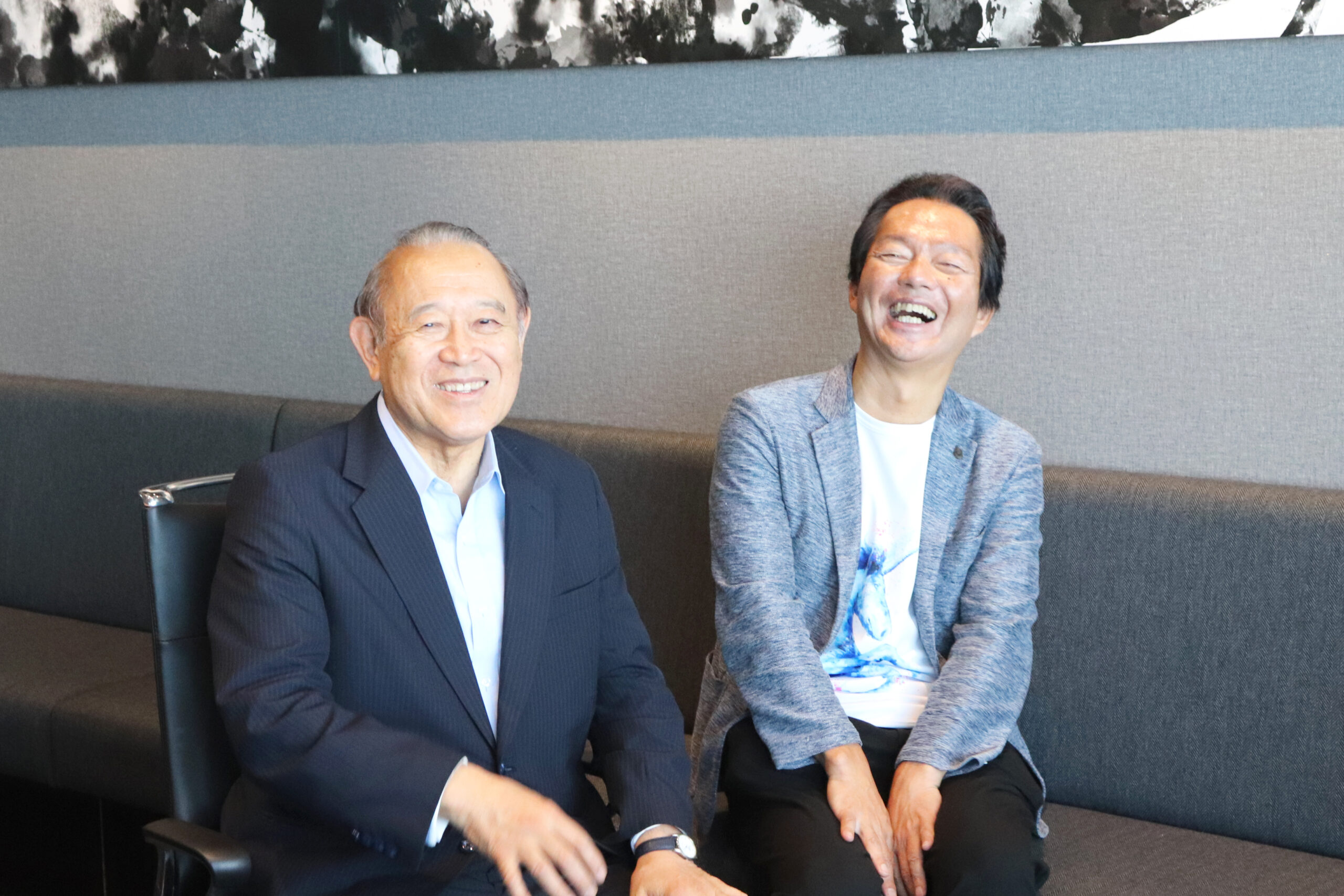

Our President and CEO Kazuhiro Goto interviewed Ichiro Fujisaki, who is a former Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Japan to the United States. Advisor Fujisaki was appointed as an advisor to D-POPS GROUP in April 2023 to help realize a Venture Ecosystem.

This article is based on the first part of the interview.

You can view Advisor Fujisaki’s profile here:

https://d-pops-group.co.jp/en/company/board-member/

President Goto:

Thank you for taking the time to have this discussion with me today.

After reading your book Mada Ma Ni Au [It’s Not Too Late] and your serial articles “Portraits of Conversation” in the Sankei Shimbun newspaper, I’m newly impressed by the depth of your experience, knowledge, and insights as an ambassador. I included some questions about diplomacy and international relations, but I felt somewhat presumptuous asking questions based on my own shallow understanding, and it made me think business leaders should just stay in their own lanes. While reading your serial articles, I was amazed by how deep and profound your interview responses were.

Advisor Fujisaki:

Could you give me an example?

Goto:

There were various points, but regarding your recent Sankei Shimbun series, in particular your article about Deng Xiaoping’s famous strategy for China’s foreign relations, coined as “taoguang yanghui” [hide your strength, bide your time], gave me a lot of food for thought.

This year, we conducted a full-scale renewal of the D-POPS GROUP corporate website. While our individual group companies had corporate websites, our main site had remained minimal. As our company grew, we were mindful of where pressure might come from, so we kept our online presence understated rather than portraying our full scale.

However, with our group now consisting of 20 companies—and nearly 50 if we include investment firms—we decided for the first time to prominently showcase our current activities on the website. Many people were surprised at how much we had expanded under the radar.

Another of your points that resonated with me was how in Japan, there’s often talk about how Japan is weak when it comes to speaking up to the US, but indeed, given that we have North Korea, Russia, and China next door, perhaps it is better for Japan and the US to maintain a consistently close relationship after all.

Fujisaki:

That’s right. There’s no other country in the world quite like Japan in this regard. It’s different from Australia or the Philippines, and different from Britain or France too. And there is only one country that has explicitly stated it will protect Japan. Therefore, we simply cannot afford to be in conflict with the US. However, I do feel that Japan tends to be overly reserved. Even within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, I advocated against excessive restraint, which sometimes led people to question why a US affairs officer would say such a thing.

Goto:

That makes sense. So, the best approach is to maintain a firm grip on relations with America on the surface, and then if there’s something you want to negotiate or discuss, you can have those conversations behind the scenes.

Fujisaki:

Exactly. And that’s probably the same with private companies or banks, isn’t it?

Goto:

Yes, that’s right. Now, while reading your interviews, I realized that the role of an ambassador, especially one to the US, requires immense personal credibility, trust, and a sense of reassurance.

This brings me to our first question: You have held numerous high-ranking positions, all of which required strong leadership. Could you share your philosophy on leadership?

Fujisaki:

To be honest, I have never been at the very top. I wasn’t a company president, prime minister, or cabinet minister. Although I was a bureau director and councilor at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and while as ambassador I flew the Japanese flag, the ultimate decision-makers were in Tokyo—the prime minister and the other cabinet ministers. So, in that sense, I wasn’t truly “plenipotentiary” despite my title.

Therefore, I’ll explain my thought process as a representative of such an organization.

First of all, one thing is that you have to effectively utilize your team. This can be quite challenging in an embassy, as it comprises officials from the Ministry of Finance; the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry; the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries; and more—not just the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Since I didn’t have authority over personnel decisions, I had to find ways to unite a team that I didn’t personally select.

To achieve this, I made a strict rule never to conduct discussions solely among Ministry of Foreign Affairs officials. Instead, I always included members from other ministries to foster open communication. And what’s crucial is bringing in the right people for the right positions as key personnel—for posts where I needed to make specific requests, I made sure to bring in people I could feel secure about.

This is because within an organization, it’s also a battle of information. The decision-making process isn’t neatly structured like a pyramid. So I made sure to bring in people I could trust to prevent various information from bypassing me.

Second, a great leader raises up the next generation. When I see even prominent leaders who don’t nurture successors and instead bring in outsiders when they leave, resulting in failure—well, I think that’s a terrible thing.

Third, leaders must anticipate the future and act before others realize the need for action. Like you, President Goto, I’ve met people from various industries and have seen many things in order to develop my intuition. The word “intuition” might sound vague, but it’s about synthesizing information, experience, and networking to recognize emerging trends. A person is not a database, so just possessing knowledge itself is not good enough. Leaders need the ability to extract meaning from their knowledge in order to anticipate the future.

Fourth, and this is important for any organization’s leader, is the ability to make decisions with good timing. Taking too long to decide can cause opportunities to slip away, while acting too hastily can lead to unnecessary risks. You have to cross at a yellow light, not a red light. The key is to decide what kind of signal you can cross at: if the light is green, everyone will cross, and your effort is wasted. Making a decision based on that discernment is essential.

Finally, leaders must continuously review and refine their decisions. Being successful once doesn’t guarantee future success. Regular progress checks and adjustments are necessary. This probably varies depending on the person.

Goto:

I often use the term “human computer”, but I don’t mean someone who makes decisions casually with only the certain information, data, etc., inside one’s head. Rather, I use it to mean determining the best answer by utilizing a vast amount of information.

Fujisaki:

I really think so. That’s why there are people who are only good at memorizing data. They were very good at studying for exams, but they are not good at synthesizing data. If you ask such a person a question, they will say, “Chapter 1 has items 1 to 10. Chapter 2 has...” I’m not asking about that; I want to know what the answer is! In this way, some people have become too much like a library. Rather, as you were saying, it is important to not only acquire data, but also to pick it out and apply it effectively. I think intuition is something like that.

Goto:

The intrigue of management may lie precisely in that aspect.

That might be what makes management so interesting. For instance, if there’s someone who is truly intelligent, possesses leadership qualities, or excels exceptionally in one area, no one can surpass that person. However, succeeding in business requires comprehensive ability—the culmination of all elements—so conversely, anyone with confidence in their overall capabilities has a chance.

Fujisaki:

You know, you don’t always have to be actively studying or trying to absorb information from books. Ideas often come to you suddenly while walking, taking a bath, or just spacing out. Of course, nothing will come to mind if you’re not thinking at all. But maybe it’s better to first build up a certain amount of knowledge, and then wait for insights to naturally emerge.

Goto:

That makes sense. When I first became a business owner and didn’t understand anything about management, I consumed an enormous amount of input. But now, I balance and regulate how much information I absorb.

Okay, here’s my next question: as Ambassador to the United States and Ambassador to the Permanent Mission of Japan to International Organizations in Geneva, there must have been many situations requiring coordination and negotiation with individual nations. Could you tell us how you managed these situations? Please share any negotiation techniques or coordination methods that are unique to you.

Fujisaki:

In negotiations, as the leader, I prioritized presenting a unified voice. I conducted most negotiations as Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs, and when I brought many people from ministries like METI and the Ministry of Agriculture for free trade agreement negotiations, I would tell them, “I’m the only one who should speak here, so don’t say anything.” In exchange, I made sure we took frequent breaks, and we would all consult together in the mornings and during lunch. In all of these general meetings, I would communicate the rule that I would be the only speaker during negotiations. After that, I would leave the sub-level and breakout meetings entirely to them and not attend those meetings myself.

Another important point is building relationships with counterpart leaders. For the first breakfast meeting, I would go alone—without any assistants—to get a general feel for the other person. Also, when those leaders came to Japan, I felt it was important to build personal relationships by doing things like going out for drinks with just the two of us. This is probably the same in business, right? There’s definitely a difference between meeting with three people on each side versus one-on-one.

Goto:

That’s for sure! In fact, a whole lot of the things you’ve said in your responses could also be said about running a business.

Let’s move onto the next question, then. How does one train and polish one’s humanity and social graces? Please share any advice you’d like to pass on to the next generation.

Fujisaki:

It isn’t false humility to say that I’m still inexperienced and have a long way to go. So, whenever I meet anyone, I try to show interest in them and avoid talking about myself from a position of superiority.

For example, my father was very devoted to improving his human qualities—he tried various things and read many books about personal development. To be honest, I haven’t reached his level yet, so I continue to strive for that on a daily basis.

My father had his own sense of aesthetics; he didn’t get caught up in trivial matters and never volunteered himself for things. His job as a Supreme Court Justice ended at age 70, and typically everyone becomes a lawyer after that. However, he didn’t pursue law at all. He just spent his time taking walks, watching TV, and reading Buddhist books—that was his style. I’m nowhere near that level…even now, I’m always busy doing things like going to school to teach classes.

Goto:

But you know, people who truly possess a depth of life experience don’t usually go around saying they’re working on their humanity. It’s something that develops naturally over time, and before you know it, you’ve built up remarkable human qualities.

In Part 2 of the interview, we cover:

• The differences between large Japanese corporations and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs

• Balancing power dynamics when dealing with multiple global superpowers

• Insights on US presidents who left a lasting impression